Caste, employment on women’s minds as turnout gap narrows

These conversations are significant not least because they offers an insight into a group marginalised on account of caste as well as gender.

Three weeks ago, in Maholi village of central Uttar Pradesh (UP), a group of Dalit women gathered to speak about who they were leaning towards in the general elections. The local Lok Sabha constituency, Sitapur, was won by the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in 1999, 2004 and 2009 but support from the Valmikis ( a Dalit sub-caste to which the women belonged), among others, helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) snatch the seat in 2014. Most of them were manual scavengers, and the primary breadwinners of their families, dependent on the local town council for wages, and as such, the party that controlled the municipality influenced their vote. But they were not happy. “After voting, the BJP leaders have not come to our village. Their local faces are all upper castes,” said Amarti Devi.

These conversations are significant not least because they offers an insight into a group marginalised on account of caste as well as gender. They also indicate that when it comes to understanding voter behaviour — particularly in states like UP, where the Samajwadi Party and BSP teamed up — the voice of women in caste groups is equally important.

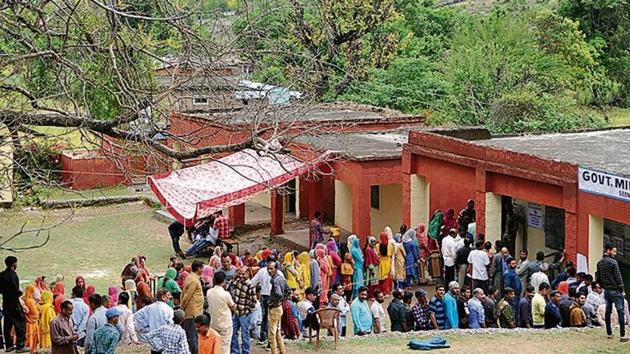

The numbers make it hard to ignore. In 2019, the gap between women and men voter turnout narrowed to its smallest margin yet. Until the fifth phase, by when 424 of 543 seats had voted, Election Commission data revealed that women’s turnout lagged by 0.3% behind men’s. The gap has been steadily narrowing— in 2009, it was 4.5%; in 2014, it was 1.7%.

The increased participation can be attributed to many reasons, such as better access to mobile phones and hence, news besides outreach by political parties.

Rajini Singh, 24, in Deogra village of Madhya Pradesh, is a keen follower of political news on social media. “See this mobile. This helps me to find on what is happening in elections. I have seen many speeches of [Narendra] Modi and Rahul Gandhi.”

A WhatsApp group is a platform to participate in political discussions. This is important particularly in light of what Sarah Khan, a doctoral researcher at the University of Columbia, considers an important factor in charting women’s electoral participation — their unwillingness to share opinions. In a working paper, Khan found that due to the lower value ascribed to household work, women’s preferences are valued differently. Women’s unwillingness to express dissenting views on political issues within the household potentially extends to outside the household, affecting their civic participation.

Megha Rajawat of Ambikapur village in Madhya Pradesh said she and her friends discuss politics and make up their own minds. Her mother, she said, voted as per the wishes of her father. “My mother is not aware of issues. I am and I argue with my father if I don’t agree with him. Many young women in my village still vote as per the family decision,” she said.

Can women be seen as a votebank? Major parties were certainly concerned with this question. In December, the Congress carried out a survey of around 40,000 women in Karauli, Rajasthan, to understand their voting behaviour. The BJP also conducted a survey in the heartland states last year. The manifestos of both parties included several promises meant for women. Both promised 33% reservation for women in Parliament and state assemblies. In the Nyay scheme, the Congress sought to transfer ₹72,000 per annum to bank accounts of women in the poorest families. The BJP spoke of women-focused schemes such as Ujjawala, which guaranteed the first LPG cylinder to poor households. But even if women-centric policies are promised, it is essential that women have greater contact with all levels of government, including being part of it. In the 1952 Lok Sabha, 4.2% out of 489 members were women; in the outgoing Lok Sabha, only 11.2% MPs were women.

In an event organized by Bangalore-based citizens’ group, Shakti, in Delhi in February, a group of women politicians across parties debated the low representation in the Parliament. Dravida Munnetra Kazagham’s Kanimozhi, who contested from Tamil Nadu, said, “The political space is not used to accommodating women... We need women to work across ideology and party lines in Parliament to help this change.”

Studies have also found that women voters tend to focus on issues like livelihood, access to water and health, and education. In a Chennai redevelopment colony, groups of women pointed at their plastic pots when a candidate came campaigning last month. “Our vote is for someone who can solve our water problem. Tell us what you will do,” they said. While there may not be a uniform women vote base, regional issues certainly shape electoral choices.